Linux Context Switching Internals: Part 1 - Process State and Memory

How does the Linux kernel represent processes and their state: A breakdown of task_struct and mm_struct

A Note from the Author:

I am also releasing this series of articles on Linux Context Switching Internals in the form of a short ebook which is currently at an early-access discount at the below link. Paid subscribers get it a discounted rate.

As a thank you, I am offering the book at a 50% discount to monthly subscribers, and 100% discount to annual subscribers. Subscribe now and I will send you a discount link:

Introduction

Context switching is necessary for a high-throughput and responsive system where all processes make progress despite limited execution resources. But, as we discussed in the previous article, it also has performance costs which cascade through various indirect mechanisms, such as cache and TLB eviction.

When building performance-critical systems or debugging performance issues due to context switching, it becomes important to understand the internal implementation details to be able to reason through the performance issues and possibly mitigate them. Not only that, it leads you to learn many low-level details about the hardware architecture, and makes you realize why the kernel is so special.

At first glance, context switching seems straightforward—save the current process's registers, switch page tables and stacks, and restore the new process's registers.

However, the reality is much more complex, involving multiple data structures, hardware state management, and memory organization. To fully grasp context switching, we need to understand few key foundational concepts about the Linux kernel and X86-64 architecture. We'll explore these through a series of articles:

Process Management Fundamentals (this article)

Process representation through

task_structVirtual memory and address space management

Key data structures for context switching

User to Kernel Mode Transition

System call and interrupt handling mechanics

Hardware state changes

Security considerations

Timer Interrupt Handling

What timer interrupts are

How the Linux kernel uses timer interrupts to do process accounting

Conditions for triggering a context switch

Context Switching Implementation

CPU register management

Memory context switches

Cache and TLB considerations

Hardware vulnerability mitigations

In this first article, we'll focus on two foundational aspects:

How the kernel represents processes using

task_structand related structuresHow process address spaces are organized and managed

Understanding these fundamentals is important because context switching is essentially the manipulation of these structures to safely transfer CPU control between processes. Let’s begin!

Processes in the Linux Kernel

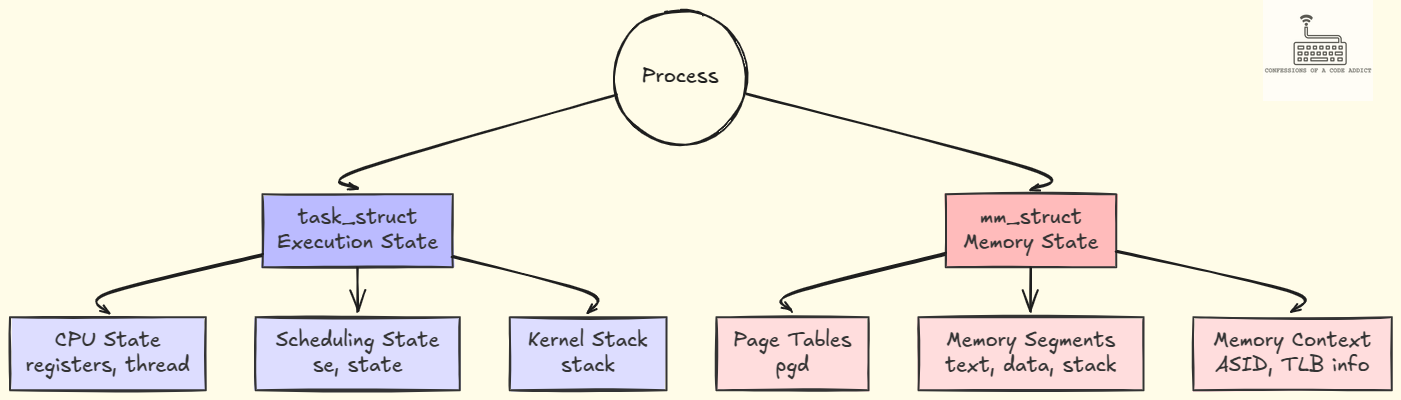

Before diving into the details, let's look at how the Linux kernel organizes process information. At its core, the kernel splits process management into two main concerns: execution state and memory state, managed through two key structures:

As shown in the diagram, process management revolves around two main structures: task_struct for execution state and mm_struct for memory management. We will start by discussing the definition of task_struct and its role in representing the execution state of the process.

Process State Management in Linux

A process is a running instance of a program. While a program is simply a binary file containing executable code and data stored on disk, it becomes a process when the kernel executes it. Each execution creates a distinct process with its own execution state—consisting of memory contents and current instruction position. This distinction is important because as a process executes, its state continuously changes, making each instance unique even when running the same program.

The Linux kernel's representation of processes reflects this dynamic nature. It defines a struct called task_struct which contains various fields to track the process state. Because task_struct is huge with dozens of fields, we'll focus on the ones most relevant to scheduling and context switching. The following figure shows a truncated definition with these essential fields.

Let’s go over these fields one by one.

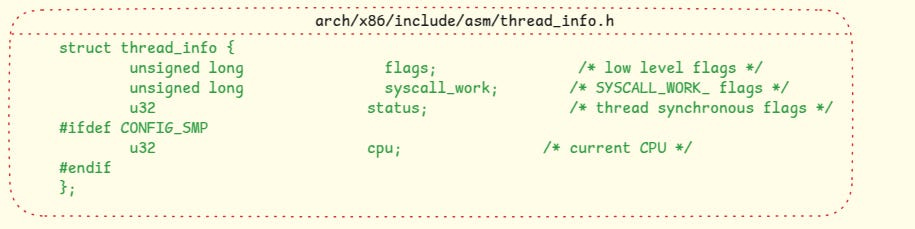

Thread Information and State Flags

The thread_info struct (shown below in figure-3) contains flag fields that track low-level state information about the process. While those flags track many different states, one particularly important flag for context switching is TIF_NEED_RESCHED.

The kernel sets this flag in thread_info when it determines that a process has exhausted its CPU time quota and other runnable processes are waiting. Usually, this happens while handling the timer interrupt. The kernel's scheduler code defines the function shown in figure-4 to set this flag.

This flag serves as a trigger—when the kernel is returning back to user mode (after a system call or interrupt) and notices this flag is set, it initiates a context switch. The code snippet in figure-5 from kernel/entry/common.c shows how the kernel checks this flag and calls the scheduler's schedule function to do the context switch just before exiting to user mode.

With the low-level state tracking handled by thread_info, let's examine how the kernel tracks the broader execution state of a process.

Process Execution States

The __state field represents the execution state of a process in the kernel. At any given time, a process must be in one of these five states:

Running/Runnable: The process is either actively executing on a CPU or is ready to run, waiting in the scheduler queue.

Interruptible Sleep: The process has voluntarily entered a sleep state, typically waiting for some condition or event. In this state, it can be woken up by either the awaited condition or by signals. For example, a process waiting for a lock enters this state but can still respond to signals.

Uninterruptible Sleep: Similar to interruptible sleep, but the process cannot be disturbed by signals. This state is typically used for critical I/O operations. For instance, when a process initiates a disk read, it enters this state until the data arrives.

Stopped: The process enters this state when it receives certain signals (like

SIGSTOP). This is commonly used in debugging scenarios or job control in shells.

Zombie: This is a terminal state where the process has completed execution but its exit status and resources are yet to be collected by its parent process.

These states are fundamental to the kernel's process management and directly influence scheduling decisions during context switches. For instance, if the currently executing process has exhausted its CPU time slice, but there are no other runnable processes, then the kernel will not do a context switch.

Process Kernel Stack

The stack field in task_struct is a pointer to the base address of the kernel stack. The stack serves two fundamental purposes in the execution of code on the CPU:

Function Local Variable Management: The stack automatically handles the lifetime of function-local variables. When a function is called, the stack grows to accommodate its local variables. Upon function return, the stack shrinks, automatically deallocating those variables.

Register State Preservation: The stack provides a mechanism for saving and restoring register values. For instance, the X86 SysV ABI mandates that before making a function call, the caller must preserve certain register values on the stack. This allows the called function to freely use these registers, and the caller can restore their original values after the call returns.

Every process maintains two distinct stacks:

User Mode Stack: Used during normal process execution when the CPU is running in process code. This stack holds the call chain of currently executing user-space functions.

Kernel Mode Stack: Used when the CPU executes kernel code in the process context, such as during system calls or interrupt handling. When transitioning from user to kernel mode, the CPU saves the user mode register values on this kernel stack (we'll cover this in detail when discussing mode transitions).

The user mode stack is tracked inside the mm field which we will discuss in the next section.

Memory Management State of the Process

The mm field points to an mm_struct object—the kernel's representation of process virtual memory (or address space). This structure is central to memory management as it contains:

The address of the process page table

Mappings for various memory segments (stack, text, data, etc.)

Memory management metadata

This data structure is one of the centerpieces of context switching as it is directly involved in the switching of address spaces. Because of this central role, we will discuss it in detail in the next section.

CPU Time Tracking

The task_struct tracks CPU usage through two fields: utime and stime. These fields record the total amount of time the process has spent executing on the CPU in user mode, and kernel mode respectively, since its creation.

A process is in user mode when the CPU is executing the process code itself, whereas it is in kernel mode when the CPU is executing some kernel code on behalf of the process, which usually happens when the process executes a system call.

Note that, these fields are not what the scheduler uses to decide when to perform context switching. The scheduler specific time tracking information is maintained inside the se field which we discuss next.

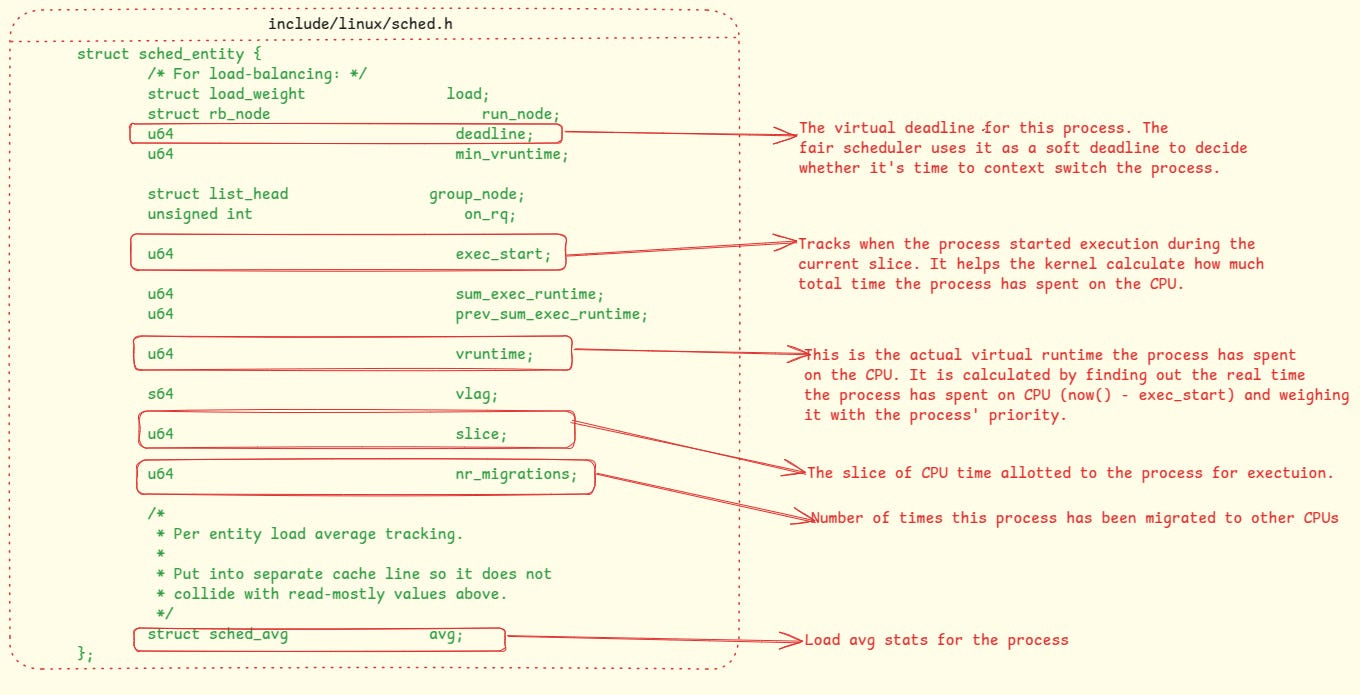

Scheduler Entity and Runtime Management

Scheduling information is managed through the se field of task_struct, which contains a sched_entity structure. While most fields in this struct are deeply tied to the scheduler implementation, we'll focus on two critical fields that directly impact context switching:

vruntime: It tracks the process's virtual runtime during its current CPU slice. This is the amount of time the process has executed on the CPU, weighted by its priority. The weighting mechanism ensures high-priority processes accumulate vruntime more slowly, thereby receiving more CPU time. For example:

A high-priority process might have its runtime weighted by 0.5

A low-priority process might have its runtime weighted by 2.0

This means that for equal actual CPU time, the high-priority process accumulates half the vruntime

deadline: This field defines the virtual runtime limit for the current execution slice. When a process's vruntime exceeds this deadline, it becomes a candidate for context switching.

The relationship between vruntime and deadline forms the core mechanism for CPU time allocation and context switch decisions.

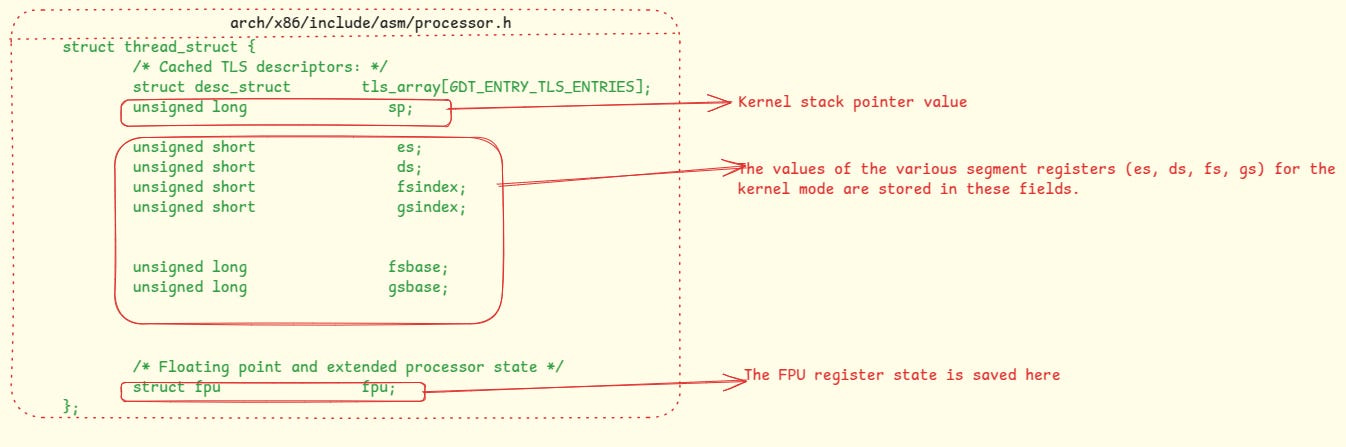

CPU State and Register Management

Context switching requires saving the hardware state of the process, and different hardware architectures have different registers and other architectural details. As a result, task_struct includes the thread_struct field to manage any architecture specific state of the process. The X86-64 definition of thread_struct is shown in figure-7.

Let’s understand the role of the fields in thread_struct:

Stack Pointer (sp):

The

spfield is used to save the value of the stack pointer register (RSPon x86-64) during context switching.It comes handy during the stack switching step of the context switch process. To switch stacks, the kernel saves the current process’s

RSPregister value in itsspfield and then loads thespfield value of the next process intoRSP. (Don’t worry if this doesn’t make sense yet—we’ll discuss this in detail in the final article of the series.)

Segment Registers (es, ds, fsbase, gsbase):

The remaining fields in the

thread_structobject are to save the kernel mode values of the segment registers (es,ds,fs, andgs) during context switching. Even though, in X86-64, segmented memory is no longer in use, these registers are still there and the kernel needs to save them for compatibility.

The

fsandgsregisters are important to understand here. They are used for implementing thread-local storage (TLS) in user space code. This is achieved by storing a base address in thefs(orgs) register. All thread-local objects are stored at an offset from this base address. These objects are accessed by reading the base address, and adding the object's offset to find the final virtual memory address.

The kernel also uses these registers in a similar fashion to implement percpu variables, which allow the kernel to track the state of processes executing simultaneously on different processors. For instance, every processor has a percpu pointer variable pointing to the currently executing process on that CPU. On whichever CPU the kernel executes, it can safely manipulate that process’s state.

For these reasons, it is important to save and restore these segment registers during context switches.

Key Points About Process Representation

Before moving on to process memory management, let's summarize the key aspects of how Linux represents processes:

Process State Management

Each process is represented by a

task_structLow-level state flags are tracked in

thread_infoProcess execution states (running, sleeping, etc.) are managed via

__state

Execution Context

Process maintains separate user and kernel stacks

CPU state is preserved in

thread_struct, which has an architecture specific definition

Scheduling Information

Virtual runtime (

vruntime) tracks weighted CPU usageDeadline determines when context switches occur

These components work together to enable the kernel to track process execution state, make scheduling decisions, and perform context switches. However, a process needs more than just CPU state to execute—it needs memory for its code, data, and runtime information. This brings us to the second major aspect of process management: the address space.

The Address Space of a Process

Before diving into mm_struct, let's understand how operating systems organize process memory. They implement memory virtualization to support concurrent process execution. Each process operates with the illusion of having access to the entire processor memory, while in reality, the kernel allocates only a portion of physical memory to it.

This is made possible using paging. The virtual memory of a process consists of pages (typically sized 4k). Any address that the process tries to read or write is a virtual address which is contained in one of these pages.

However, in order to perform those reads and writes, the CPU needs to know the physical addresses in the main memory where the data is actually stored. For that, the hardware translates the virtual address into physical address. It does this via the page table which maps the virtual memory pages to physical pages.

Figure-8 shows an example of a 2-level page table, but note that for X86-64, the Linux kernel uses a 4 (or sometimes 5) level page table to be able to address large amounts of physical memory.

User and Kernel Page Table

Now, it turns out that a process may have two page tables, one for user mode execution and another for kernel mode. This is similar to how it has a user mode stack and a kernel stack. During a transition from user to kernel mode, both the stack and the page tables need to be switched to their kernel counterparts.

The separate kernel page table was introduced as a security measure following the Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities. These attacks showed that malicious user-space processes could potentially read kernel memory through speculative execution side channels. By maintaining separate page tables, the kernel memory becomes completely isolated from the user space, effectively mitigating such vulnerabilities.

Segments of a Process’s Memory

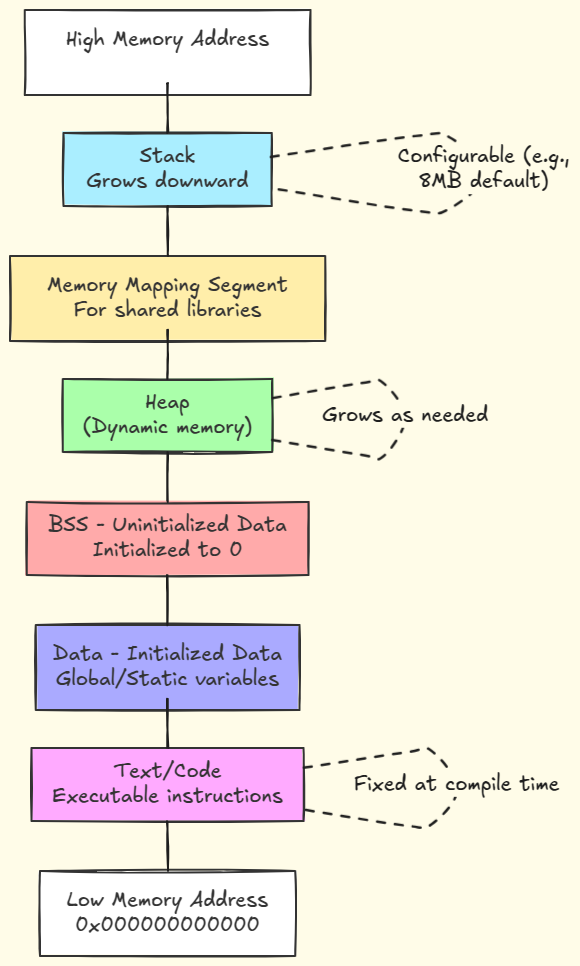

Beyond page tables, a process needs its code and data mapped into its address space before it can execute. This mapping follows a specific layout where different types of data occupy distinct memory regions called segments. Figure-9 shows a detailed view of the memory layout of a process.

Each segment is created by mapping a set of pages for it, and then loading the corresponding piece of data from the program’s executable file. Let’s go over some of the key segments and understand their role in the process’s execution.

The Stack Segment

This is the user mode stack of the process, used for the automatic memory management of function local variables, and saving/restoring registers when needed.

Unlike the kernel mode stack, the user space stack does not have a fixed size, and can grow upto a limit. Growing the stack involves mapping more pages for it.

While the stack manages function execution context, processes also need memory for dynamic allocation, for which the heap segment is used.

Dynamic Memory: Heap

The heap area is used for dynamic memory allocation. Unlike most other segments in the process’s memory which are loaded with some kind of process data, the heap starts empty. But durings its execution, the process may dynamically allocate memory using malloc or similar functions, and the allocated memory may come from this region.

Beyond dynamic memory, processes need space for their static data, which leads us to the data segment.

Static Data Segments

Any program consists of two kinds of data that is part of the compiled binary. These are global variables and constants initialized to a non-zero value, and other data which is either initialized to zero, or uninitialized but defaults to a zero value.

The non-zero initialized data is mapped into the data segment of the process, while the zero initialized (or uninitialized) data goes into the BSS segment.

Code Segment (Text)

Finally, the code segment is where the executable code of the program is loaded. The protection mode of the pages backing this segment is set to read-only and execute so that no one is able to modify the executable code once it loaded into memory, as this can be a potential security risk.

When multiple processes are executing the same code, typically, they share their text segment pages. It saves memory and is more efficient.

With an understanding of these conceptual components, let's examine how the Linux kernel implements this memory organization through its mm_struct structure.

Memory Management Implementation in Linux

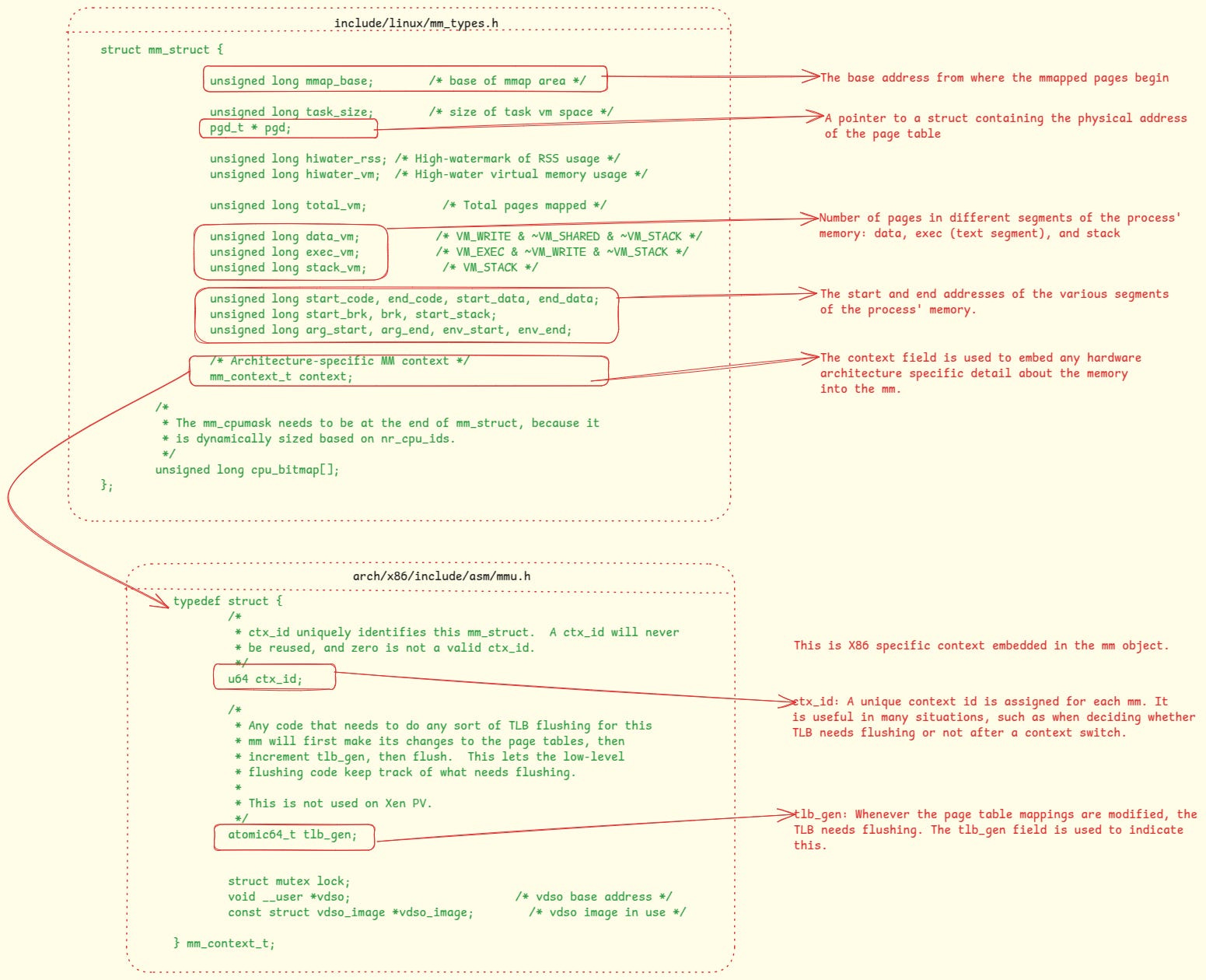

The kernel encapsulates all this memory management information in the mm_struct structure. This is also a very large struct, so we'll focus on the fields crucial for context switching. Figure-10 shows a truncated definition of mm_struct with only the fields we are interested in.

Let’s discuss these fields, and see how they map to what we discussed about virtual memory.

Page Table Directory (PGD)

The pgd field in mm_struct contains the physical address of the page table directory—the root of the process's page table hierarchy. This address must be physical rather than virtual because the hardware MMU directly accesses it during address translation.

During context switches, this field is crucial as it enables the kernel to switch the CPU's active page table, effectively changing the virtual memory space from one process to another. The kernel loads this address into the CR3 register, which immediately changes the address translation context for all subsequent memory accesses.

Memory Segment Boundaries

We saw how the memory of a process is organized in the form of segments. The mm_struct object tracks the boundaries of these segments by maintaining their beginning and ending addresses.

Stack Segment:

start_stack is the base address of the user mode stack. Note that there is no field to track the end of the stack because unlike other segments, the stack can dynamically grow during the execution of the process. Also, the CPU tracks the address of the top of the stack using the RSP register, so it always knows the end of the stack.

Code Segment:

start_codeandend_code: These fields provide the bounds of the code (text) segment where the executable instructions of the program are loaded.

Data Segment:

start_dataandend_data: These fields form the bounds of the data segment.

Architecture-Specific Memory State

The context field (mm_context_t) handles architecture-specific memory state. For X86-64, it contains two key fields which are critical during context switches, as they help the kernel decide if a flush of the translation lookaside buffer (TLB) is needed or not.

TLB is a small cache in the CPU core which caches the physical addresses of recently translated virtual addresses. The cache is crucial for performance because a page table walk for doing address translation is very expensive.

The two fields in mm_context_t definition for X86-64 are:

ctx_id

Every process’s address space is assigned two identifiers. One is a unique id stored in the ctx_id, and the other is a pseudo-unique id called address space identifier (ASID), which is a 12-bit id.

The hardware uses the ASID to tag the entries in the TLB which allows storing entries for multiple processes without requiring a flush. The ASID value ensures that the hardware will not let one process access another process's physical memory. In the absence of the ASID mechanism, a TLB flush is mandatory across context switches.

But the ASID is just 12-bit wide and has only 4095 possible values, as a result it needs to be recycled by the kernel when it runs out of available values. This means that while a process is switched out of CPU, its ASID may get recycled and given to another process.

When a process is being resumed back as part of context switch, the kernel uses its ctx_id to find the ASID value that was assigned to the process during the previous slice of execution. If that ASID has not been recycled, a TLB flush is not needed. But, if the process has to use a new ASID, a TLB flush needs to be done.

tlb_gen

The tlb_gen field is a generation counter used to track page table modifications. Each CPU maintains a per-CPU variable recording the tlb_gen value for its current/last used mm_struct.

When the kernel modifies page table mappings (e.g., unmapping pages or changing permissions), it increments tlb_gen in the mm_struct. This indicates that any CPU's cached TLB entries for this address space might be stale.

When a CPU switches to running a process, it compares its stored tlb_gen (if it has one for this mm_struct) with the mm_struct's current tlb_gen. If they differ, or if this CPU hasn't recently run this process, it flushes its TLB to ensure it doesn't use stale translations.

The explanation provided for these fields might not make a lot of sense yet. But don’t worry, we will revisit it and discuss these in more detail in the last part of the series.

This completes our discussion of how the Linux kernel represents process memory state. We've seen how mm_struct orchestrates virtual memory, from page tables to memory segments, and how it handles architecture-specific requirements for efficient memory access.

Having examined both task_struct and mm_struct in detail, Let's summarize what we've learned and look at what comes next.

Putting It All Together

We've covered the two fundamental data structures that the Linux kernel uses to represent processes and their execution state:

task_struct: The process descriptor that contains:

Execution state (running, sleeping, etc.)

CPU time tracking (user and system time)

Scheduling information (sched_entity)

Architecture-specific thread state

Kernel stack location

mm_struct: The memory descriptor that manages:

Page table information

Memory segment locations

TLB and cache management metadata

These structures work together during context switches. For example:

The scheduler uses

task_struct'ssched_entityfield to track process’s virtual runtimeThe

thread_infoflag indicates when switching is neededThe

thread_structobject contains the CPU specific state that needs savingThe

mm_struct's context determines if TLB flushes are required

Looking Ahead

Understanding these data structures is crucial because they're at the heart of context switching operations. In our next article, we'll explore how the CPU transitions between user and kernel mode, specifically:

How system calls and interrupts trigger mode switches

The role of interrupt handlers

How the kernel saves user state

CPU protection mechanisms during transitions

Performance implications of mode switching

We'll see how the fields we discussed in task_struct and mm_struct are actually used during these transitions, and how they enable the kernel to safely switch between different execution contexts.

Additional Resources

For readers interested in diving deeper:

The Linux source code: torvalds/linux/include/linux/sched.h

Intel's Software Developer Manual, particularly Volume 3A, Chapter 4 (Paging)

The book "Understanding the Linux Kernel" by Daniel P. Bovet and Marco Cesati

In our next article, we'll build on this foundation to understand the mechanics of user-to-kernel mode transitions.

Support Confessions of a Code Addict

If you find my work interesting and valuable, you can support me by opting for a paid subscription (it’s $6 monthly/$60 annual). As a bonus you get access to monthly live sessions, and all the past recordings.

Subscribed

Many people report failed payments, or don’t want a recurring subscription. For that I also have a buymeacoffee page. Where you can buy me coffees or become a member. I will upgrade you to a paid subscription for the equivalent duration here.

I also have a GitHub Sponsor page. You will get a sponsorship badge, and also a complementary paid subscription here.