How PyTorch Generates Random Numbers in Parallel on the GPU

A deep dive into Philox and counter-based RNGs

GPUs power modern deep learning models because these models rely on tensor operations, which can be efficiently parallelized on GPUs with their thousands of cores. However, apart from tensor computations, these models also rely on random numbers. For example, to initialize the model weights, during dropout, data sampling, stochastic gradient descent, etc.

So, the question arises: how do frameworks like PyTorch generate random numbers in parallel on GPU devices? Because if random number generation becomes a bottleneck, it can significantly slow down the entire training or inference pipeline.

The answer lies in a clever algorithm called Philox, a counter-based parallel random number generator. In this article, we’ll explore:

Why traditional random number generators don’t parallelize well

How Philox works and what makes it different

How to parallelize random number generation using Philox

PyTorch’s implementation of Philox by dissecting its C++ and CUDA code

By the end, you’ll understand how that simple torch.randn() call efficiently generates millions of random numbers in parallel on your GPU while maintaining perfect reproducibility.

Cut Code Review Time & Bugs in Half (Sponsored)

Code reviews are critical but time-consuming. CodeRabbit acts as your AI co-pilot, providing instant Code review comments and potential impacts of every pull request.

Beyond just flagging issues, CodeRabbit provides one-click fix suggestions and lets you define custom code quality rules using AST Grep patterns, catching subtle issues that traditional static analysis tools might miss.

CodeRabbit has so far reviewed more than 10 million PRs, installed on 2 million repositories, and used by 100 thousand Open-source projects. CodeRabbit is free for all open-source repo’s.

Problem with Traditional PRNGs

Let’s start by developing an intuition about why traditional pseudo random number generators (PRNGs) are sequential and not suitable for parallel hardware, such as GPUs.

A PRNG needs to be able to reproduce the same sequence of random numbers when initialized with a specific seed. A natural way of achieving this is through a state transformation function that takes the current state of the generator as input and produces a new state. As long as the function is deterministic, it is guaranteed that we can reproduce the exact same sequence of numbers starting from the same initial state. Mathematically, it can be expressed like this:

Here, the next state is derived by applying the function f on the current state s_n. As you can see, this is a sequential model where you can’t jump ahead arbitrarily without computing all the previous states, and you can’t shard the generation of the random numbers by distributing the work across threads.

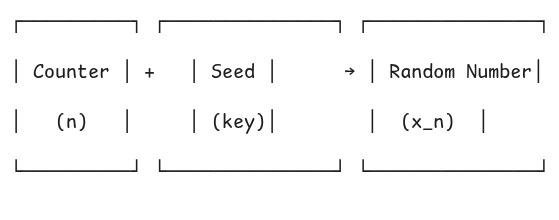

To parallelize the generation of random numbers, we need a different model where we can directly generate the nth random number without having to go through the generation of all the previous n-1 numbers. Mathematically, it should look like this:

Where x_n is the nth random number we wish to generate by applying a function b. Here, we can think of the input n as an integer counter and as such the PRNGs that follow this model are called counter-based random number generators. One such counter-based PRNG is the Philox PRNG, used widely in frameworks such as PyTorch for parallel random number generation on GPUs.

Let’s understand how Philox works.

How Philox Works

The Philox algorithm, short for “Product HI, LOw, with XOR”, is a counter-based PRNG that was designed specifically for parallel computation. It was introduced by Salmon et al. in 2011 as part of the Random123 library. The key insight behind Philox is that we can use a cryptographic-like construction to transform a counter into a pseudorandom number.

The Core Idea: Treating RNG as Encryption

We can think of the counter-based RNG problem this way: we want to take a sequence of integers (0, 1, 2, 3, …) and scramble them so thoroughly that they appear random. This is conceptually similar to what a block cipher does in cryptography, it takes a plaintext message and a key, then produces a ciphertext that looks random.

In Philox’s case:

The counter (n) acts like the plaintext

The seed acts like the encryption key

The output is our pseudorandom number

The beauty of this approach is that any thread can independently compute its random number by knowing just two things: which counter value it needs (its position in the sequence) and the seed. No synchronization or communication with other threads is needed.

The Philox Construction

Philox operates on fixed-size inputs and outputs. The most common variant is Philox-4x32, which means:

4: Works with 4 32-bit integers at a time

32: Each integer is 32 bits wide

So Philox-4x32 takes a 128-bit counter (represented as four 32-bit integers) and produces a 128-bit output (four 32-bit random numbers). This is perfect for generating multiple random numbers at once, which is common in GPU workloads.

The algorithm consists of applying multiple rounds of a transformation function. Each round performs these operations:

Multiplication and splitting: Multiply pairs of the input integers and split the results into high and low parts

XOR with keys: XOR certain parts with key-derived values

Permutation: Shuffle the positions of the integers

Let’s break down a single round in detail. Philox-4x32 works with four 32-bit values, which we’ll call (c0,c1,c2,c3). Each round transforms these values through the following steps:

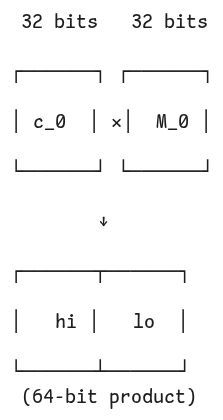

Step 1: Multiply and Split

Take the first pair (c0,c1) and the second pair (c2,c3). Multiply each by a carefully chosen constant:

For Philox-4x32, these constants are:

M0=0xD2511F53

M1=0xCD9E8D57

These constants were chosen through careful analysis to ensure good statistical properties. When we multiply two 32-bit numbers, we get a 64-bit result. We split this into:

High 32 bits: hi(prod)

Low 32 bits: lo(prod)

Step 2: XOR with Keys

The high parts are XORed with round-specific keys derived from the seed, and with the other input values:

Here, k0 and k1 are the key values (derived from the seed), and ⊕ represents the XOR operation.

Step 3: Permutation

Finally, we rearrange the values for the next round. The output of one round becomes:

Notice how the values are shuffled: the low parts of the products go to positions 0 and 2, while the XORed high parts are swapped and go to positions 1 and 3.

Multiple Rounds

To achieve good randomness, Philox-4x32 typically applies 10 rounds of this transformation. After each round except the last, the keys are also updated:

Where w0=0x9E3779B9 and w1=0xBB67AE85 are the “Weyl sequence” constants derived from the golden ratio. This ensures that each round uses different key material, increasing the mixing of the input bits.

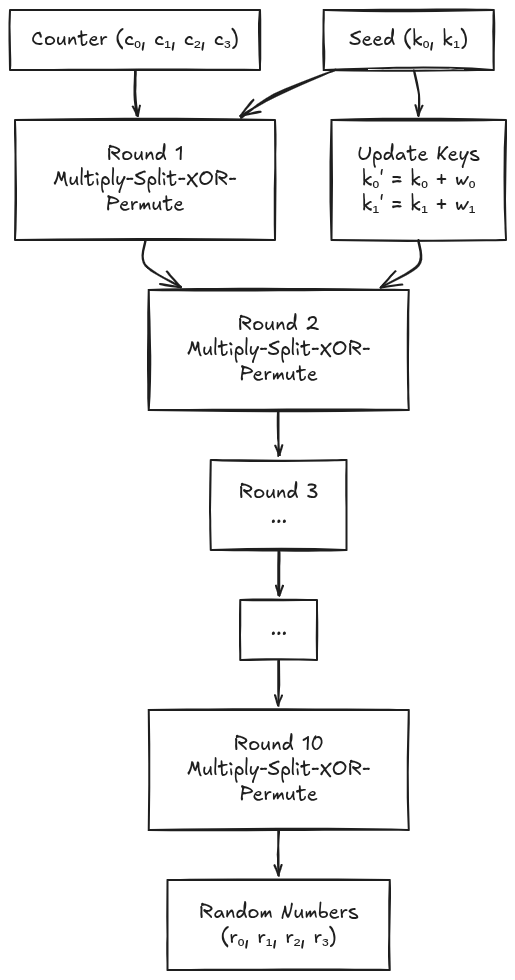

Visualizing a Complete Philox Transformation

The following diagram shows the complete flow through multiple rounds:

Why This Works

The Philox algorithm achieves good randomness through several mechanisms:

Multiplication is a non-linear operation that mixes bits effectively. Small changes in input lead to large changes in output.

High-low splitting ensures we use all 64 bits of the multiplication result, not just the lower 32 bits.

XOR operations combine different data streams (keys, previous values) in a way that’s invertible but unpredictable without knowing the key.

Permutation ensures that the mixing effect propagates to all output positions across rounds.

Multiple rounds compound these effects, ensuring that every output bit depends on every input bit in a complex way.

The algorithm has been extensively tested and passes standard statistical tests for randomness like the TestU01 suite, making it suitable for scientific computing and machine learning applications.

Properties of Philox

Before we dive into PyTorch’s implementation, let’s summarize the key properties that make Philox attractive:

Parallel-friendly: A GPU with thousands of cores can generate thousands of random numbers simultaneously, each using a different counter value.

Deterministic: Given the same seed and counter, you always get the same output.

Long period: With a 128-bit counter, you can generate 2^128 random numbers before the sequence repeats numbers, more than enough for any practical application.

Fast: The operations (multiplication, XOR, bit shifting) are primitive operations that run very efficiently on modern CPUs and GPUs.

Memory efficient: The generator state is just the counter and key, requiring minimal storage per thread.

Next, let’s understand how Philox can be parallelized.

Parallelizing Philox: Subsequences and Offsets

Now that we understand how the Philox algorithm works, let’s explore what makes it particularly powerful for parallel computing: the ability to generate random numbers across thousands of threads simultaneously without any coordination.

The Random Number Space

Recall that Philox is a counter-based PRNG. At its core, it’s a function that maps a 128-bit counter to a 128-bit random output:

Given a fixed key (derived from the seed), each unique counter value produces a unique set of random numbers. Since we have a 128-bit counter, we have:

Each counter value produces 4 random 32-bit numbers (since 128 bits = 4 × 32 bits), giving us an enormous space of random numbers. We can visualize this as a huge one-dimensional array:

Counter: 0 1 2 3 ... 2^128-1

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

Output: [r₀,r₁,r₂,r₃][r₄,r₅,r₆,r₇][r₈,r₉,r₁₀,r₁₁][r₁₂,...]...[...]

How do we partition this massive space across parallel threads? One approach is to split the counter space between the threads.

Partitioning the Counter Space

The key insight is that we can split the 128-bit counter into two parts and use them to create a 2D address space. Think of the counter as having 4 components of 32 bits each: (c0,c1,c2,c3).

We can partition this as:

Upper 64 bits: Which thread’s region we’re in

Lower 64 bits : The position within a thread’s assigned region

This partitioning scheme gives each thread its own “slice” of the random number space:

Thread 0 gets counters: (∗,∗,0,0) where ∗∗ can be any value

counter = (0,0,0,0) → first 4 random numbers for thread 0

counter = (1,0,0,0) → next 4 random numbers for thread 0

counter = (2,0,0,0) → next 4 random numbers for thread 0

…

Thread 1 gets counters: (∗,∗,1,0)

counter = (0,0,1,0) → first 4 random numbers for thread 1

counter = (1,0,1,0) → next 4 random numbers for thread 1

counter = (2,0,1,0) → next 4 random numbers for thread 1

…

Thread 2 gets counters: (∗,∗,2,0)

counter = (0,0,2,0) → first 4 random numbers for thread 2

And so on…

Terminology: Subsequence and Offset

We now give names to these two parts:

Subsequence: The upper 64 bits of the counter. This identifies which parallel thread or stream we’re referring to. We can have up to 2^64 different subsequences running in parallel.

Offset: The lower 64 bits of the counter. This identifies the position within a subsequence. Each subsequence can generate up to 2^64 sets of random numbers.

Together, they form a coordinate system (s,o) where:

s is the subsequence (which parallel stream)

o is the offset (position in that stream)

The total capacity is:

This matches exactly the size of our original counter space, we’ve simply reorganized it into a 2D structure that’s easy to partition across threads.

How Offsets Increment

When a thread generates more random numbers, it increments the offset portion of the counter. Since Philox generates 4 random numbers at once, we typically increment by 1 each time (remembering that each offset value produces 4 numbers):

Thread 0 subsequence = 0:

offset=0: counter=[0,0,0,0] → Philox → [rand₀, rand₁, rand₂, rand₃]

offset=1: counter=[1,0,0,0] → Philox → [rand₄, rand₅, rand₆, rand₇]

offset=2: counter=[2,0,0,0] → Philox → [rand₈, rand₉, rand₁₀, rand₁₁]

...

The offset is really tracking “which batch of 4” we’re on. If we need the 10th random number (index 9, counting from 0):

Offset = ⌊9/4⌋=2

Position within batch = 19mod4=1

So we use counter [2,0,0,0] and take the second output (index 1)

The Power of Skip-Ahead

One powerful consequence of this design is skip-ahead: a thread can jump directly to any offset without computing intermediate values.

Thread 0:

- Jump to offset 1,000,000: counter = [1000000, 0, 0, 0]

- Generate random numbers at this position

- Jump to offset 5,000,000: counter = [5000000, 0, 0, 0]

- No need to compute offsets 1 through 4,999,999!

This is impossible with traditional sequential PRNGs where state n+1n+1 depends on state nn.

Setting Up for PyTorch

Now that we understand how the counter space is partitioned, we can see how PyTorch uses this:

When PyTorch generates random numbers on a GPU:

It launches many threads (e.g., 1024 threads)

Each thread is assigned a unique subsequence number (typically its thread ID)

Each thread starts at offset 0 within its subsequence

As each thread generates random numbers, it increments its offset

PyTorch tracks the global offset to ensure future operations don’t reuse the same counters

With this foundation, let’s now explore how PyTorch implements these concepts in its Philox engine.

Philox Implementation in PyTorch

PyTorch uses Philox-4x32-10 (4 values of 32 bits, 10 rounds) as its primary PRNG for CUDA operations. The implementation lives in aten/src/ATen/core/PhiloxRNGEngine.h and is designed to work on both CPU and GPU (via CUDA). Let’s dissect this implementation to understand how the theoretical concepts we discussed earlier translate into actual code.

Core Data Structures

The implementation starts by defining some type aliases for clarity:

typedef std::array<uint32_t, 4> UINT4; // Four 32-bit integers

typedef std::array<uint32_t, 2> UINT2; // Two 32-bit integers

typedef std::array<double, 2> DOUBLE2; // Two doubles

typedef std::array<float, 2> FLOAT2; // Two floats

These typedefs make the code more readable. UINT4 represents the 128-bit counter or output (4 × 32 bits = 128 bits), while UINT2 represents the 64-bit key (2 × 32 bits = 64 bits).

The PhiloxEngine Class Structure

The philox_engine class maintains four critical pieces of state:

private:

detail::UINT4 counter_; // 128-bit counter (c₀, c₁, c₂, c₃)

detail::UINT4 output_; // Cached output from last round

detail::UINT2 key_; // 64-bit key derived from seed (k₀, k₁)

uint32_t STATE; // Position in current output (0-3)

Let’s understand each field:

counter_: This is the 128-bit counter that gets incremented and transformed through the Philox rounds. It’s divided into four 32-bit components:

counter_[0]andcounter_[1]: Lower 64 bits represent the offset (which random number in the subsequence)counter_[2]andcounter_[3]: Upper 64 bits represent the subsequence (which parallel stream)

key_: The 64-bit key derived from the seed. This remains constant for a given seed and is used in the XOR operations during each round.

output_: Philox generates 4 random 32-bit numbers at once. This field caches those numbers so we don’t have to recompute them for every call.

STATE: A simple counter (0-3) that tracks which of the four cached output values to return next. This is an optimization to avoid regenerating when we have unused random numbers.

Initialization and State Management

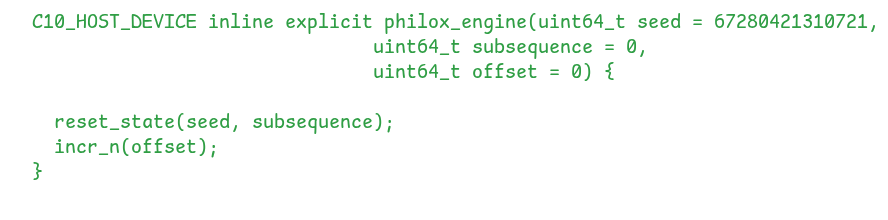

The constructor initializes the engine with a seed, subsequence, and offset:

The C10_HOST_DEVICE macro is crucial here, it tells the compiler that this function can run on both the CPU (host) and GPU (device). This allows the same code to be used in both contexts.

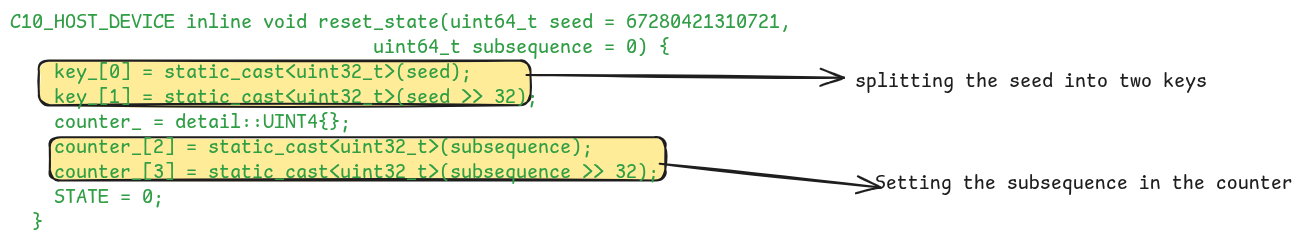

Let’s look at how reset_state sets up the initial state:

This initialization strategy is clever:

The seed is split into the two key components

key_[0]andkey_[1]The subsequence goes into the upper half of the counter (

counter_[2]andcounter_[3])The offset (lower half of counter) starts at zero but can be set later via

incr_n(offset)

This design allows for massive parallelism. Imagine running 1024 CUDA threads simultaneously:

Thread 0: subsequence=0, offset=0 → counter = [0, 0, 0, 0]

Thread 1: subsequence=1, offset=0 → counter = [0, 0, 1, 0]

Thread 2: subsequence=2, offset=0 → counter = [0, 0, 2, 0]

...

Thread 1023: subsequence=1023, offset=0 → counter = [0, 0, 1023, 0]

Each thread has a unique counter value from the start, so they all generate independent random sequences without any coordination.

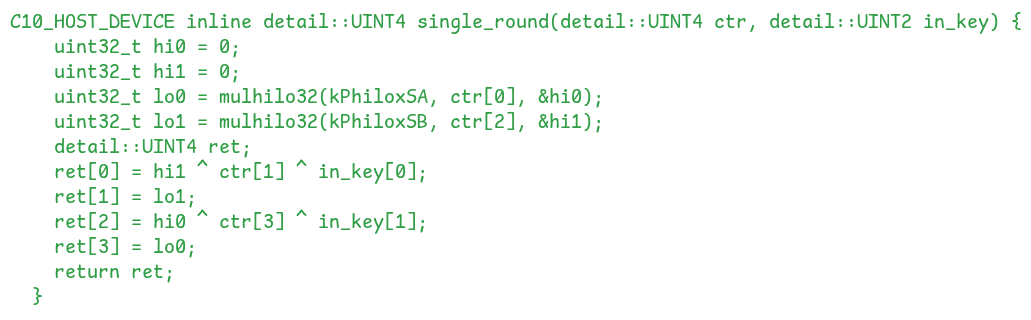

The Core Algorithm: Single Round

Now let’s examine the heart of the Philox algorithm—the single_round function:

Let’s break this down step by step, mapping it to our earlier theoretical description:

Step 1: Multiply and Split

uint32_t lo0 = mulhilo32(kPhiloxSA, ctr[0], &hi0);

uint32_t lo1 = mulhilo32(kPhiloxSB, ctr[2], &hi1);Here we multiply:

ctr[0]bykPhiloxSA(the constant 0xD2511F53)ctr[2]bykPhiloxSB(the constant 0xCD9E8D57)

The mulhilo32 function performs the multiplication and splits the 64-bit result:

Returns the low 32 bits (

lo0orlo1)Stores the high 32 bits in the passed pointer (

hi0orhi1)

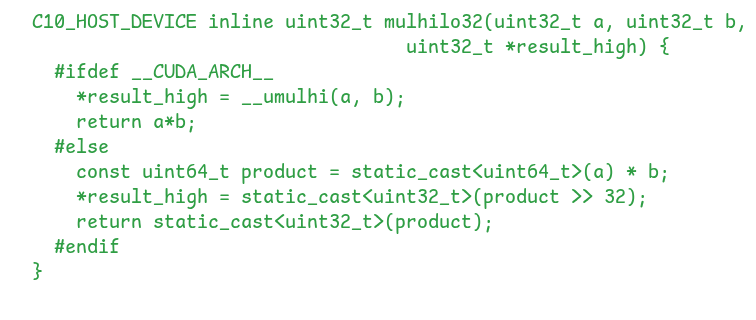

Let’s look at mulhilo32 itself:

This function has two implementations:

On CUDA (GPU): Uses the intrinsic __umulhi which directly computes the high 32 bits of a multiplication. This is extremely fast on GPU hardware.

On CPU: Promotes both operands to 64 bits, multiplies them, then extracts high and low parts manually via shifting and casting.

Here’s what happens mathematically:

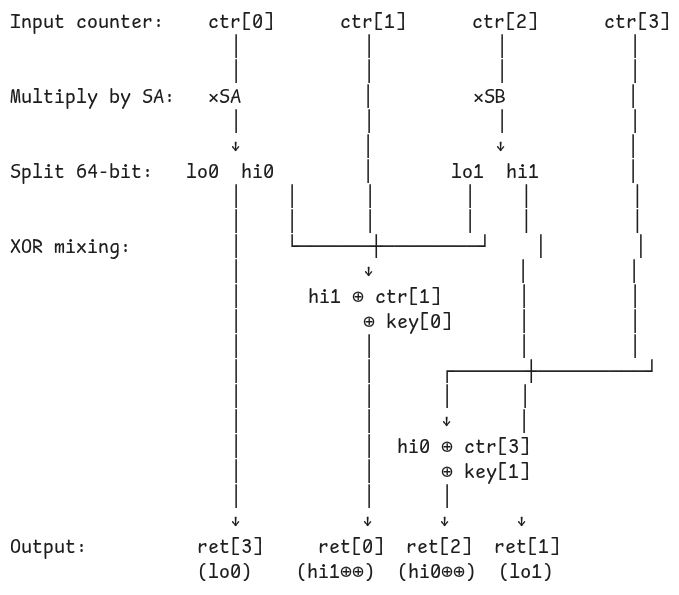

Step 2: XOR and Permute

ret[0] = hi1 ^ ctr[1] ^ in_key[0];

ret[1] = lo1;

ret[2] = hi0 ^ ctr[3] ^ in_key[1];

ret[3] = lo0;Notice the pattern:

ret[0]: Takeshi1(high bits from second multiplication), XORs withctr[1]andin_key[0]ret[1]: Simply useslo1(low bits from second multiplication)ret[2]: Takeshi0(high bits from first multiplication), XORs withctr[3]andin_key[1]ret[3]: Simply useslo0(low bits from first multiplication)

Let us visualize this transformation:

This permutation ensures that bits from different positions get mixed together in subsequent rounds.

Constants: The Magic Numbers

You might wonder where these constants come from:

static const uint32_t kPhilox10A = 0x9E3779B9; // Weyl sequence

static const uint32_t kPhilox10B = 0xBB67AE85; // Weyl sequence

static const uint32_t kPhiloxSA = 0xD2511F53; // Multiplier

static const uint32_t kPhiloxSB = 0xCD9E8D57; // Multiplier

Weyl sequence constants (kPhilox10A and kPhilox10B): These are derived from the golden ratio. The constants are:

The golden ratio has special properties that make it useful for distributing values uniformly. These constants are added to the key after each round to ensure different key material is used.

Multiplier constants (kPhiloxSA and kPhiloxSB): These were carefully chosen through empirical testing to maximize statistical quality. They need to have good bit-mixing properties when multiplied with typical counter values.

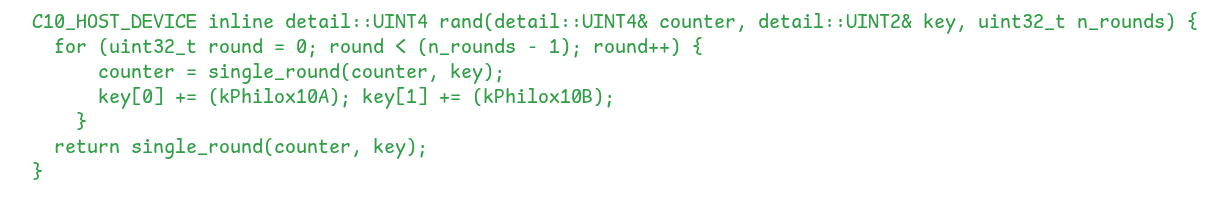

Running Multiple Rounds

The rand function orchestrates running all rounds:

This is straightforward:

Run

n_rounds - 1iterations where we:Apply

single_roundto transform the counterUpdate the key by adding the Weyl constants

Apply one final round without updating the key

By default, PyTorch uses 10 rounds (n_rounds = 10), which provides a good balance between performance and statistical quality.

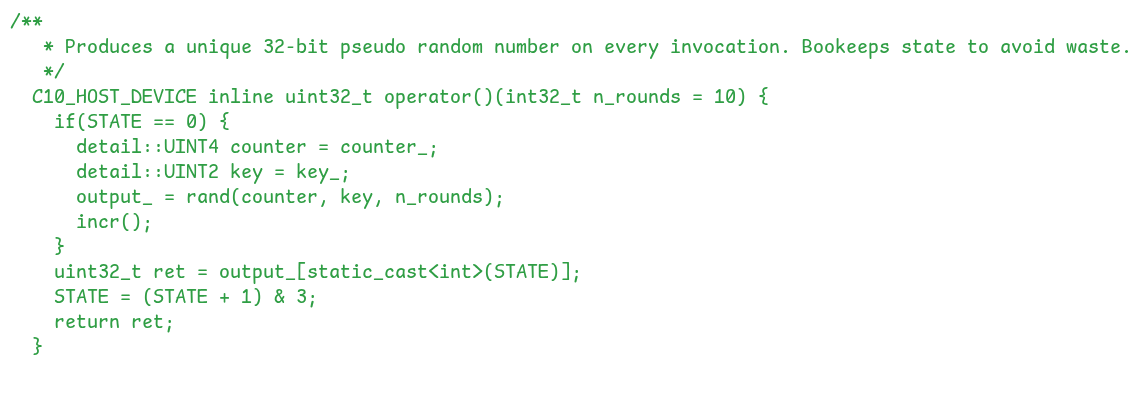

Generating Random Numbers: The Operator

The operator () is what users call to get random numbers:

This function is clever in its efficiency:

Check if we need new random numbers: if(STATE == 0) checks if we’ve exhausted the previous batch. Remember, STATE cycles through 0, 1, 2, 3.

Generate a batch: When needed, it:

Runs the full Philox algorithm via

rand(counter, key, n_rounds)Stores the result in

output_(four 32-bit random numbers)Increments the counter for next time via

incr()

Return next value: Grab the current position from output_, then advance STATE.

The line STATE = (STATE + 1) & 3 is a bit trick equivalent to STATE = (STATE + 1) % 4, using bitwise AND since 3 is binary 11.

This batching strategy is a significant performance optimization. Instead of running Philox for every random number, we run it once per four random numbers.

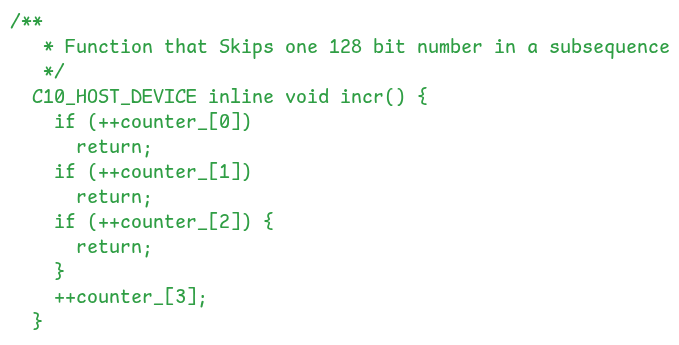

Counter Increment Logic

The counter increment operations deserve special attention because they handle the 128-bit arithmetic correctly. Let’s start with the simple case:

This increments the 128-bit counter by 1. The logic is:

Increment

counter_[0](least significant 32 bits)If it’s non-zero after increment, we’re done (no overflow)

If it overflowed to zero, carry to

counter_[1]Continue propagating carries until we find a non-zero result

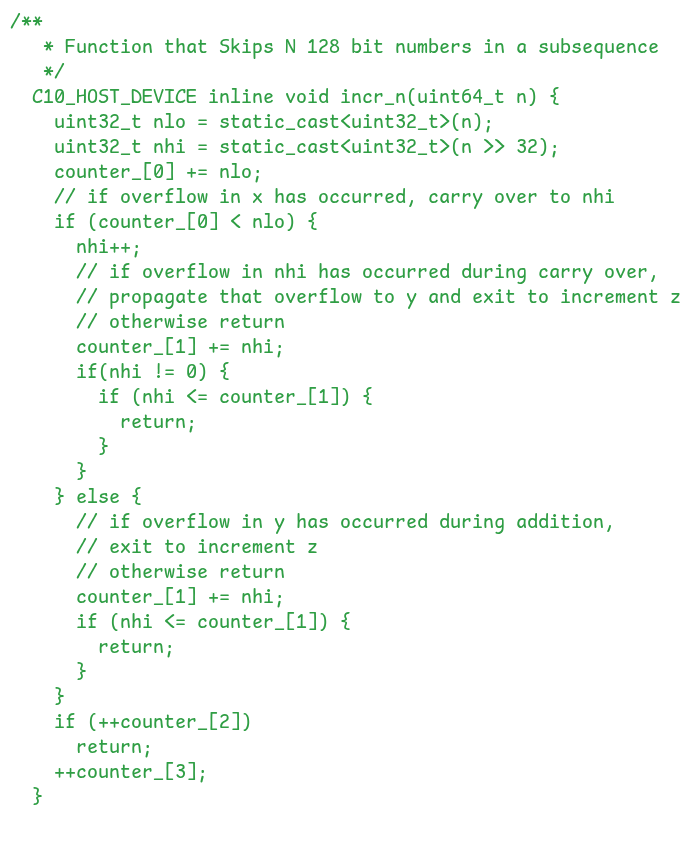

The more complex function is incr_n, which increments by an arbitrary 64-bit value:

This function is more intricate because it needs to:

Split the 64-bit increment

nintonloandnhiAdd

nlotocounter_[0]Detect overflow by checking if

counter_[0] < nlo(if the result is less than what we added, overflow occurred)If overflow, increment

nhito carry overAdd

nhitocounter_[1]and check for overflow againIf still overflowing, propagate to the upper 64 bits

The overflow detection counter_[0] < nlo is a standard technique in multi-precision arithmetic. After adding, if the result is less than one of the operands, an overflow must have occurred since we’re working with unsigned integers.

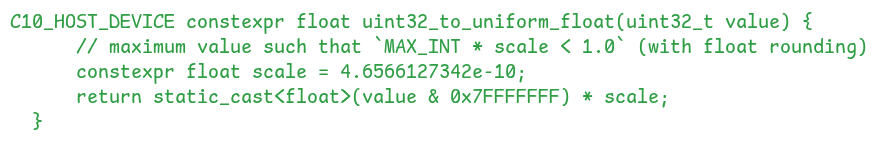

Converting to Floating Point

For machine learning applications, we often need floating-point random numbers in the range [0, 1), while Philox gives us integers. So, PyTorch applies a conversion function:

This function is carefully designed:

Mask off sign bit: value & 0x7FFFFFFF clears the highest bit, giving us values from 0 to 2^31−1

Scale down: Multiplying by scale = 4.6566127342e-10 maps these integers to floats in [0, 1).

The scale factor is calculated as:

Why use only 31 bits instead of all 32? Because:

We want only positive values (for [0, 1) range)

The highest representable float less than 1.0 needs careful handling

Using 31 bits avoids potential rounding issues near 1.0

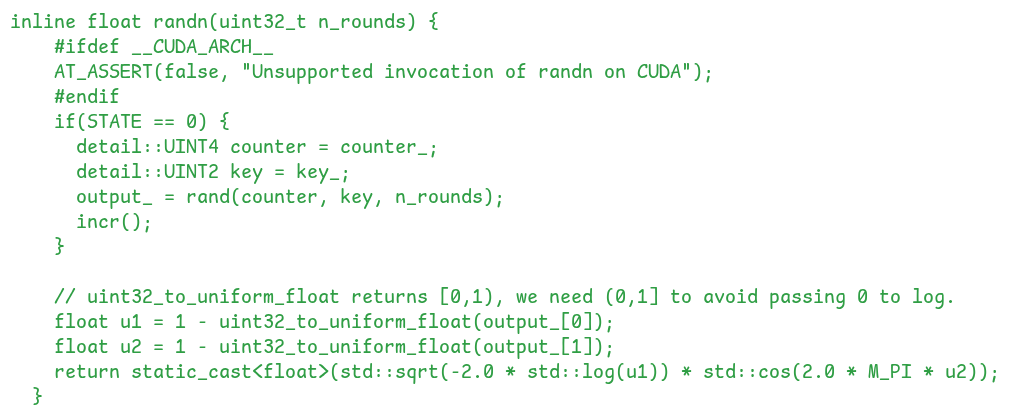

Normal Distribution Generation

The randn function generates normally distributed random numbers using the Box-Muller transform:

The Box-Muller transform converts two uniform random variables U1,U2∼Uniform(0,1) into a normal random variable Z∼N(0,1):

Memory Layout and Efficiency

One of the beauties of this implementation is how compact the state is. Each philox_engine instance requires:

counter_: 4 × 4 bytes = 16 bytes

output_: 4 × 4 bytes = 16 bytes

key_: 2 × 4 bytes = 8 bytes

STATE: 4 bytes = 4 bytes

Total = 44 bytesThis is tiny! On a GPU, you could have millions of these generators running in parallel, each consuming only 44 bytes. In comparision, traditional RNGs can take kilobytes of state per instance.

Summary

In this article, we explored Philox, a counter-based PRNG designed for parallel computing environments. We learned:

Why traditional PRNGs don’t parallelize well: Sequential state dependencies create bottlenecks on parallel hardware like GPUs.

How Philox works: By treating random number generation as a function

f(counter, key), Philox allows direct computation of any random number without computing predecessors.The algorithm’s core operations: Multiplication with carefully chosen constants, high-low splitting, XOR with key material, and permutation, repeated for 10 rounds to ensure statistical quality.

Parallelization through counter partitioning: The 128-bit counter space is split into subsequences (upper 64 bits) and offsets (lower 64 bits), allowing up to 2^64 parallel threads each generating 2^64 random numbers.

PyTorch’s implementation: A compact 44-byte state per engine instance, efficient batching of 4 numbers at a time, and careful handling of counter arithmetic for both CPU and GPU execution.